Picturing Me – Project Background

A conversation with Sarah Sandring / Galerie im Saalbau Neukölln, Berlin

Film (13 min, 2015, Language: Punjabi, Sub German)

Order the Picturing Me booklet

Informationen on the Baba Nanak Educational Society (BNES)

Ms. Sandring, a German documentary filmmaker working with children in Punjab – how did this collaboration come about?

This constellation is not unusual for me. I often work with people on location looking at their own stories, both in film and photography. It’s an intense exploration of the possibilities of visual language, working autobiographically and with the stories that make up a place. The result is a wonderful intertwining of my artwork with the work created by the participants. These projects oscillate between documentary and art and the results are often very touching and direct – more than an outsider’s view could be. I find this to be especially true working with children. They often point at things adults are too afraid to mention.

Let’s speak specifically about the project – tell us more about its background and the development of the idea for Picturing Me.

In 2012, I was in India to learn more about the situation of small farmers. I’m interested in our relationship to earth/soil as one of the origins of our existence and I’m trying to find out why we are increasingly estranging ourselves from it. Farmer suicide is an extreme example of this estrangement – something not only happening in India.

Vandana Shiva – an environmental activist who has been working for years regarding small farmers, preservation of traditional seed varieties, fighting bio piracy etc. – introduced me to Inderjit Singh Jaijee, founder of the Baba Nanak Educational Society (BNES). Mr. Jaijee himself is landowner and human rights activist. His team has been working since the 90’s to document the farmer suicides in their area of southern Punjab and support the bereaved.

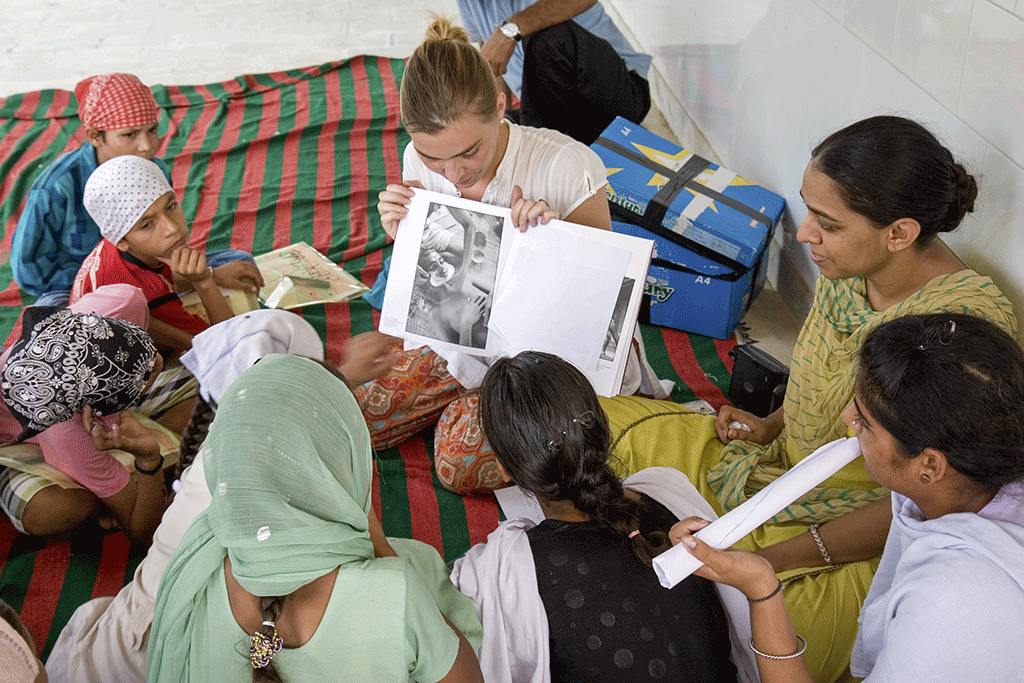

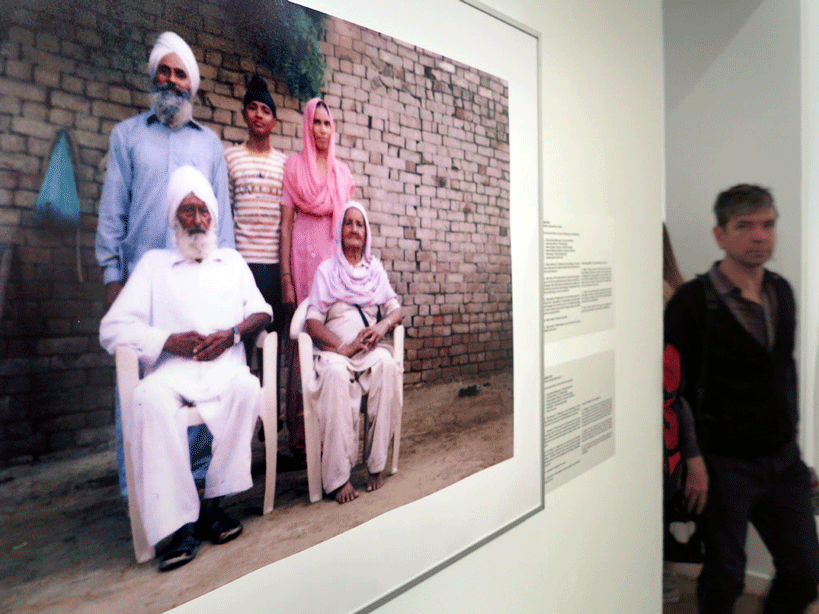

I explained to him my idea to conduct a photography project with children of a village with a high number of suicides. However, I didn’t want the project to focus on the problem itself but rather explore life in the village in its complexity. Together, we chose the village of Chotian as project location – it has one of the highest farmer suicide rates in the area. Another reason was that I met Jaspreet Kaur in Chotian, a courageous, outspoken young woman who speaks very good English. She became our on-location partner. Jaspreet had lost both her father and her uncle to suicide. The third member of the project team was Navneet Kaur Jeji, an artist and art professor in the city of Patiala. The three of us conducted the workshops with the children together. Without these partnerships, projects like this wouldn’t be possible.

In some photos and texts you can feel the distinct story of a person, others merge to form a whole. How were the participants chosen?

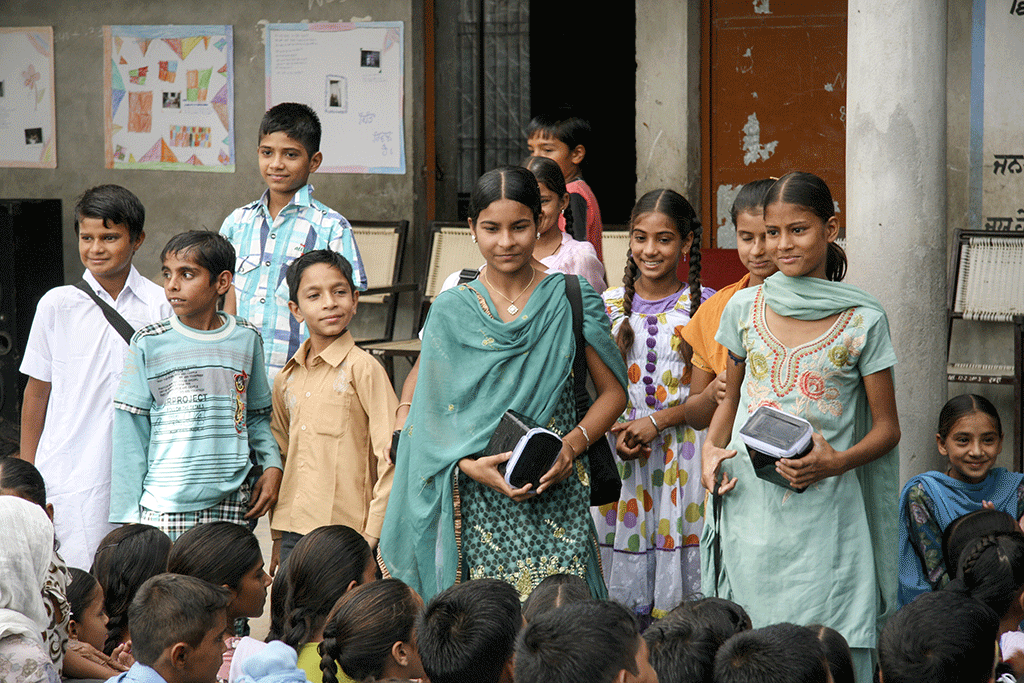

The choosing of the participants was a painful process. Over 70 children between the ages eight to 15 applied but we only had space for 15 children. We asked all children who wanted to apply, to describe an image, which had left an impression on them for one reason or another. We also asked them why they wanted to learn photography. We were looking for a diverse group – children with very different family backgrounds, religions, parents’ professions. Three of the 15 participants had lost their fathers to suicide. Others had other severe family problems. And yet others were growing up very protected. I think you can sense these differences in their works. The aim was to find an intrinsically human connection: What do the children laugh about? What are they proud of? How do they show love? I am convinced that these emotional encounters can make an audience interested in the situation ‘behind’ the images.

You worked with the children over a period of two months. How did you go about it?

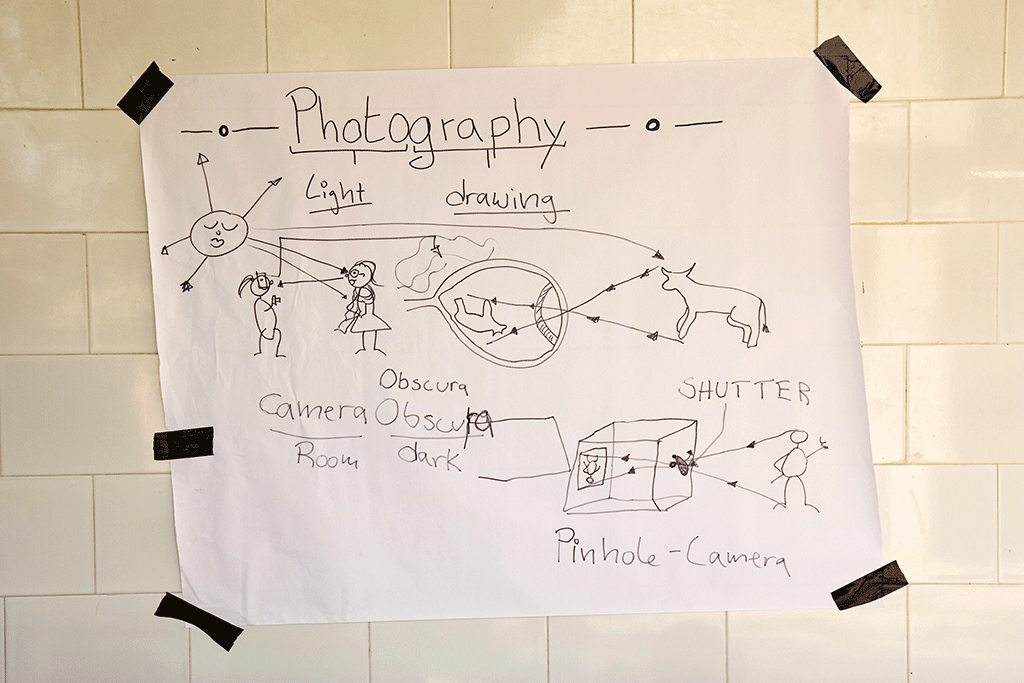

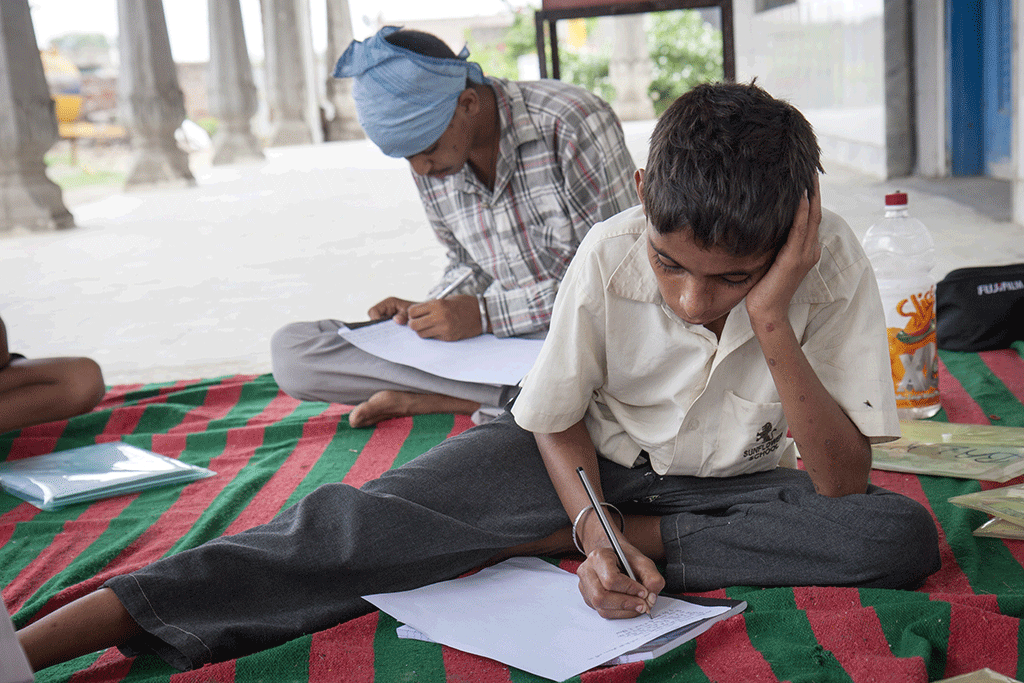

It’s central to the project that it combines writing and image making. That was important for both, the photographic process as well as for guiding the children to certain spaces within themselves. The process of writing enables you to do other things than photography. Both processes can lead to and complement one-another.

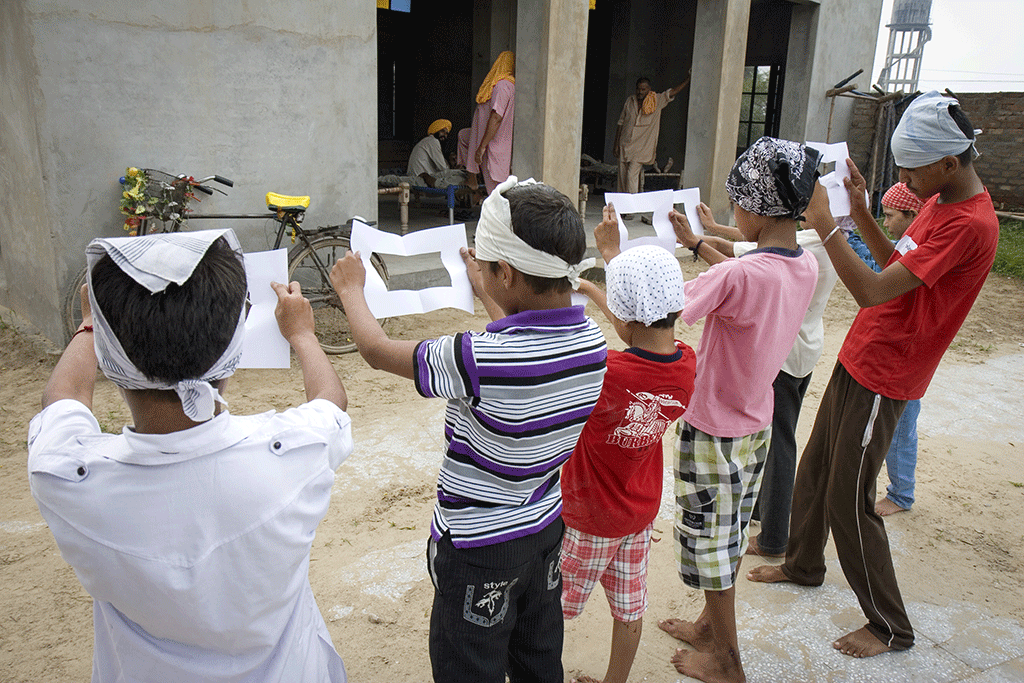

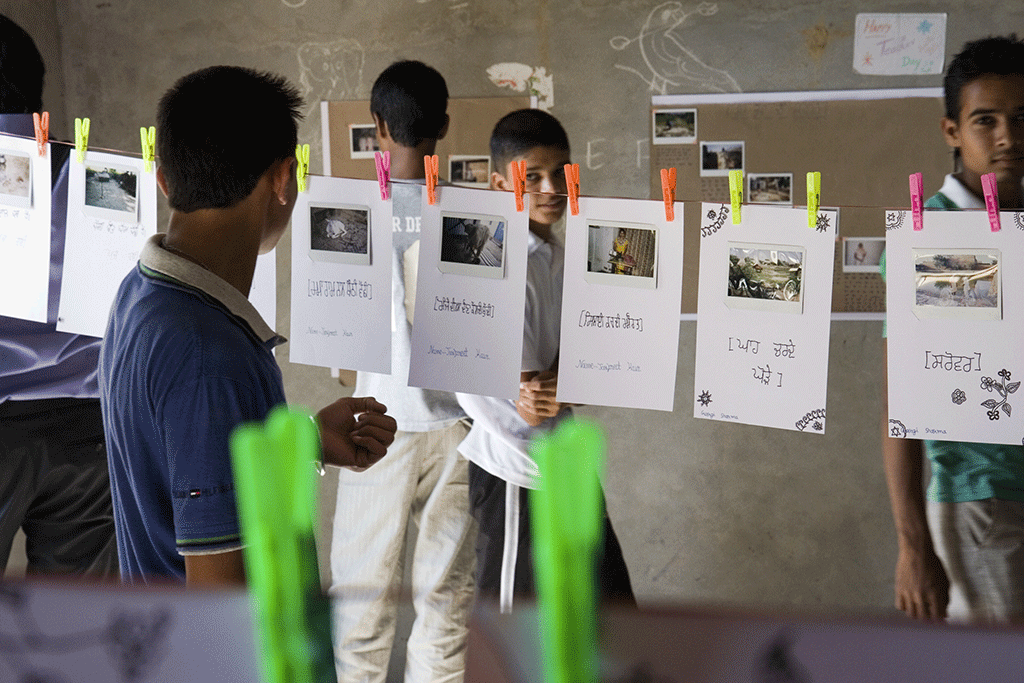

We met on the weekends and in the middle of the week. The workshops were held in the arcade of the local Gurudwara – the Sikh temple. We started by exploring the children’s individual stories and sense of ‘self’: What makes me ‘me’? Why is my view of the world important? Then we moved on to exploring ‘family’ and eventually ‘village’. Finally, the children started keeping a photographic diary. At the beginning, everything was very ‘controlled’. The children were supposed to plan ahead and think about their photograph: How do I want to photograph my subject? Where is the edge of the frame? What body posture, facial expression? What’s in the background, foreground etc.? After a while, they worked independently.

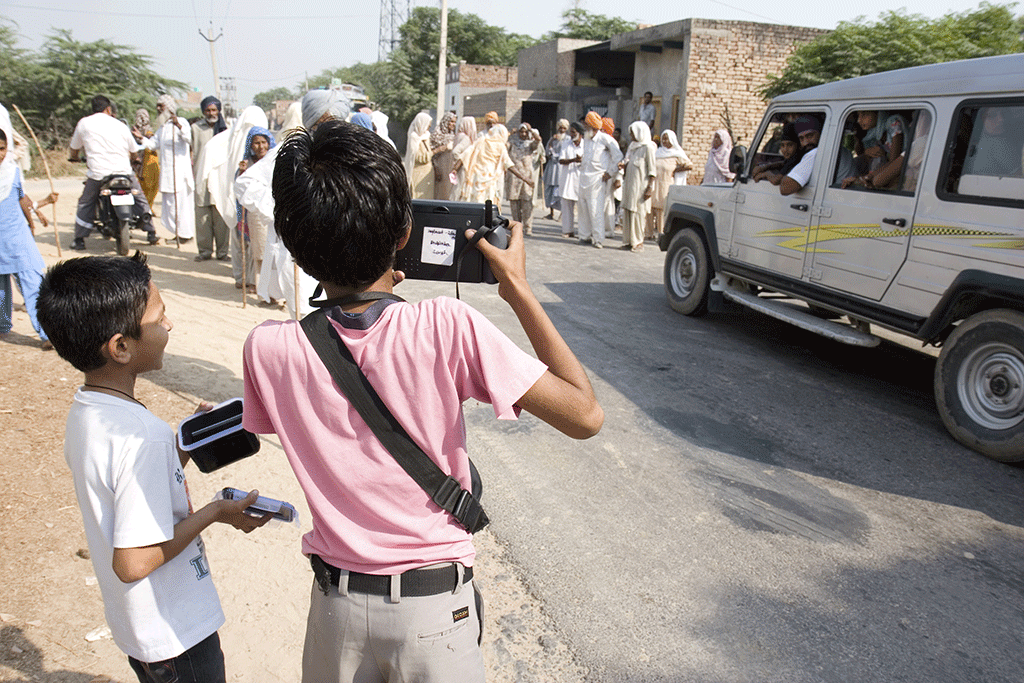

We used instant cameras, which are wonderful because they are so simple to use. The children can concentrate on the image itself. They immediately have a result they can see and show to others. Two children shared a camera and everybody had a ‘magic black box’ in which they placed the exposed photograph. The chemicals develop better when the Polaroid is not in the sun; the whole process turned into something like a magical ritual.

The children used writing and drawing to prepare the photographs. After the picture was taken, they – in turn – wrote about it. It’s a process that helps to reflect about yourself and the choices you make when clicking a picture. We always evaluated the photos together. The children loved reading their writing to the rest of the group. They also started writing their own fantasy stories – sometimes pages long! This kind of expression has no room in the Indian school system.

US-American artist Wendy Ewald developed using this combination of writing and photography. Ewald calls her approach Literacy Through Photograph. I was inspired by her work. We complemented her methods with games, drawing and using our body to experience the world – I worked closely with a German special education teacher. Otherwise, how are you supposed to teach a complicated concept like ‘perspective’ to a child? If you use your body, this is easy.

Working in another country and language was probably not easy. What were the challenges in this project?

Indeed, translation was necessary on at least two levels – language-wise and especially culturally. I have to listen closely and pay attention to what local customs demand of me in order to establish a relationship of trust, not to provoke unnecessary conflict. As a foreign woman I have more freedoms than women in the village, still it’s important to accept certain limits and your role within the constellation. Hence I became ‘madam’, which wasn’t weird for anybody but me.

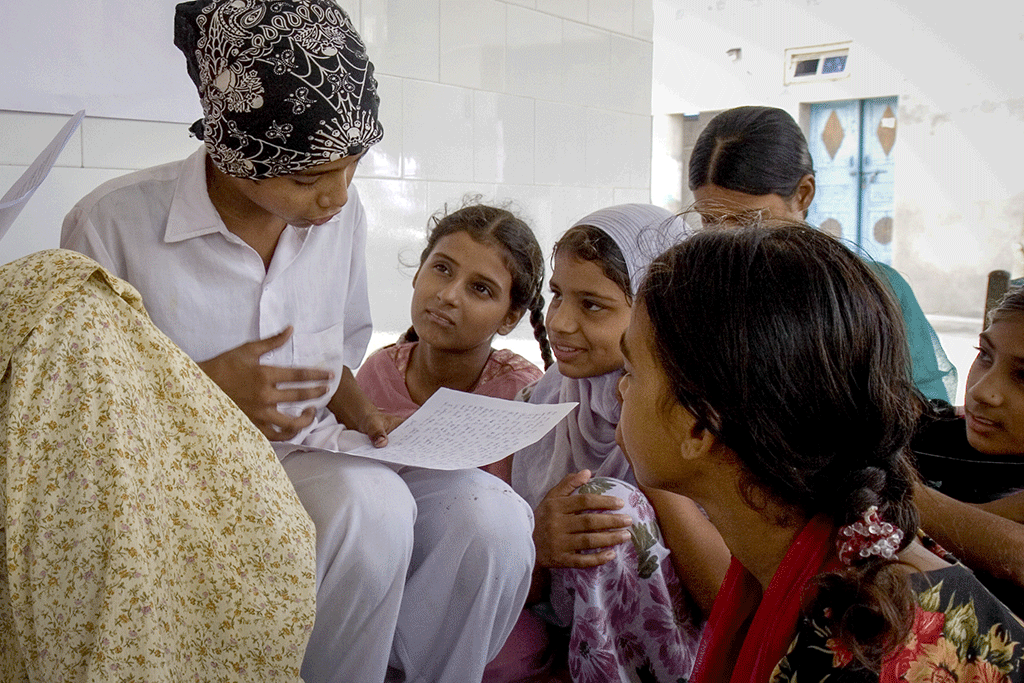

Over the weeks, we were able to loosen the hierarchical structure a bit among the 15 participants. Girls and boys started talking more freely and helping each other. They were sitting mixed in a circle instead of separated by rows of boys and girls. Their self-confidence increased. They bossed around the old men in the village streets in order to get the picture exactly the way they wanted. The change was amazing! I learned a lot from them.

From the beginning, we were concerned how to best respond to the painful stories we knew would emerge through the process. It was important to ensure the children that this was an environment of trust – we would catch them if we led them to difficult places in their mind. For example, we gave them the option to share their writing only with the workshop leaders and not the whole group. However, it’s not always easy to immediately detect a critical situation when a translation process is in between. Sometimes days passed before I learned what a child had written. In the end, all of the children were very courageous and wanted their writings to be published.

Also, the summer was very hot, up to 47°C. This was hard to handle for both – the chemistry and the humans.

How was Picturing Me funded?

The project budget was small. It was made possible by donations collected via the crowd-funding platform Betterplace.org and the support of the Delhi-based Nishkam Sikh Welfare Council as well as the already-mentioned BNES.

Finally, you often hear about the so-called parachute projects. Bluntly: well-meaning foreigners coming to exotic countries to do ‘good’ and leaving after it’s over. How can you evaluate the success of a project like Picturing Me?

That’s an important question. One of the first things I ask myself at the beginning of a project is: “Why me?” Isn’t somebody on location more suitable? I try to answer that question for myself as truthfully as possible. It influences the entire process.

Personally, I question community-art projects that simply hand out video- or photo cameras and say, “Now you are empowered – go ahead and take pictures!” The results are snapshots, which may be interesting and sometimes even ingeniously unconventional but they are coincidence. I think it’s important that there is a serious learning process, which enables participants to learn the tools they have as photographers. This way, they can make conscious decisions how to tell a certain story in a photograph and go beyond the obvious.

I’m deeply convinced that art can create an emotional connection beyond cultures and countries. To be able to ‘feel with somebody’ is immensely important to understand other people and to eliminate prejudices. Can art save the world this way? Maybe a little – it can definitely open hearts and that’s always healthy. The mind follows.

We discuss all concerns among the project team and with the participants and try to find possibilities to make the project as sustainable and long-term as possible. I’m a big fan of transparency and also of pointing out weaknesses. The people can then decide for themselves whether they want something or not. The photographers of Picturing Me are immensely proud their work is being shown in Europe. For that, they agreed to lend out their originals for a long time. The friendship and partnership to the people on location remains and, in the end, they are the ones to decide whether and how they want to continue the project. Cameras and films are still in Punjab.

It’s clear that we need a change of perspective if the visual language and word language concerning communication of so-called development issues. Perhaps the German government is on the right path by founding the Innovationsbeirat (Council of Innovation), which brings together scientists, social leader and artists like filmmaker Tom Tykwer. It shows that art is a powerful resource and is an essential part of bringing cultures together.